By Ian Ronayne

Jersey’s Forgotten History

Dominating the recent history of the charming British Channel Island of Jersey is its traumatic occupation by German forces during the Second World War. The dark days of 1940 to 1945 rightly hold an overwhelming position in the island’s collective consciousness, and are the subject of numerous books, events and museums.

Yet a mere twenty-five years earlier, Jersey had endured another global conflict. Although the island escaped any direct fighting or occupation, the impact of the First World War on this small community was traumatic nonetheless, and left a deep legacy. It is only now, more than ninety years after it ended, that the forgotten story of Jersey in the First World is starting to re-emerge.

The Challenge of War

In common with most other places in Europe, the outbreak of war in August 1914 took the island of Jersey largely by surprise. Shaken from its prosperous sojourn, in the course of barely a week the small community faced a series of unprecedented shocks. Families suffered heartbreak as thousands of French and British army reservists departed to rejoin their units marching to war. Daily life turned upside down as the island’s Militia mobilised to stand guard over the coast and key installations. People panicked as a run on banks and shops threatened to destabilise the economy. Most worrying of all, however, was the seemingly unstoppable German advance on Paris, and the threat posed to the Channel coast beyond.

Fortunately, by September, the situation had improved as firm measures at home together with an Allied victory in France eased concerns. With the threat of invasion from the Continent receding and no sign of the German fleet venturing into the Channel, thoughts turned to how Jersey might contribute to the war.

Raising a Contingent

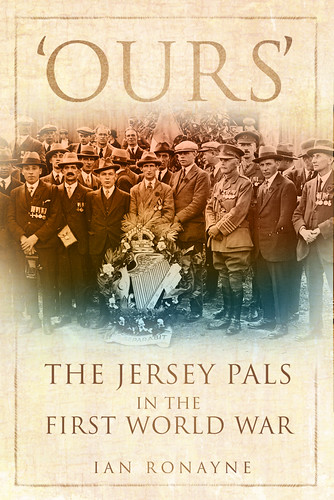

General Kitchener’s recruitment drive and formation of the famous ‘Pals’ battalions in Britain pricked the conscience of many islanders who questioned the need to retain a large force of trained Militiamen at home. In December 1914, therefore, Jersey had set about raising its own ‘Pals’ unit. By March 1915, there were 230 volunteers – enough to form an infantry company. Later joined by a further 96 men, the Jersey Company, as it was called, became part of the 7th Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles.

After training in Ireland and Aldershot, the Jersey Company went to war at the end of 1915. For the next three years, the volunteers served in the trenches and fought in some of war’s fiercest engagements. In 1916, during the Battle of the Somme, grievous losses occurred during the bitter fighting for the villages of Guillemont and Ginchy. The following year, there was triumph at Messines Ridge and then tragedy in the Passchendaele and Cambrai offensives as attacks ended in bloody failure. Following a transfer to the 2nd Battalion of the Hampshire Regiment in January 1918, the dwindling band of volunteers continued serving in France and Belgium. During the first half of that year, they fought in momentous battles to stem the massive German offensive, in the second taking part in the Allied final advance to victory. At war’s end, a handful of survivors joined the march into Germany.

Unexpected Visitors

In 1915, as the Jersey Company left for service overseas, another group of soldiers had arrived in the island. At the start of the war, island authorities received orders to prepare a camp for holding a consignment of German prisoners of war. Built on land in St Ouen’s Bay and considered a model design, Blanche Banques POW Camp soon held more than 1,000 German prisoners. Their arrival in March 1915 proved something of a novelty as scores of curious islanders turned out to see their new neighbours. Eventually the prisoners became a common sight as working parties travelled by train each day from the camp to work at St Helier’s docks.

The camp was also the cause of some local excitement. On a number of occasions, German prisoners managed to escape their confines and hide-out in the countryside. None, however, managed to get off the island. Promptly caught, they ended up back in their camp by the beach. In 1919, the last of the Germans left the island. At least one returned however, during the Second World War. One of the commandants of German forces occupying Jersey surprised local authorities by announcing he had visited their island before – as a prisoner of war!

The War Bites

As the war dragged on without showing any sign of ending, the challenges increased. Jersey, as a mainly agricultural community, was reasonably well-placed to ensure adequate food stocks for its population during wartime. It was not, however, completely self-sufficient, relying on imports of essentials such as flour, meat and margarine, as well as coal for fuel. As the German submarine campaign in the Channel intensified, there were some shortages and genuine concern that the island might face difficulties during the winter months.

Shortages of another kind would also bring about a dramatic change in the island. Britain needed men to fight the war, and women to serve in the munitions industry and as nurses. By the end of 1915, Jersey had sent its contingent, plus hundreds of other volunteers who had chosen to join up as individuals rather than as part of a representative group. Many others, both men and women, left to work in Britain’s war-related industries. Yet given the insatiable natute of this new industrialised war, there remained the demand for more. With volunteering drying up – in both Jersey and Britain – the answer lay in forcible military conscription.

Early in 1916, Britain introduced a Military Service Act allowing the government to conscript men directly into the armed forces. When it came to its Crown Dependencies, Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man, the British government expected the same rules to apply. Jersey patriotically responded to the call, and set about introducing a law of its own. After hundreds of years of autonomous government, however, the island wanted to retain much of the control over who went to war and who stayed. This led to a row between the Jersey and British authorities that rumbled on throughout much of 1916. Eventually, at the end of that year, Jersey gave in and handed over its former responsibilities to the British Military authorities. In February 1917, seven hundred years of history ended when the Jersey Militia disbanded and Britain fully took over responsibility for the island’s defence.

Digging for Victory

One of the arguments against Britain taking over control of local conscription was that Jersey needed to retain sufficient men in the island to ensure it could feed its population and meet the demands of the British government for increased agricultural yields. The largest crop by far was the famous Jersey Royal Potato, prior to the war the island’s leading export. In 1916, the British government stipulated the tonnage required for its home market, with increasing quotas for the years following. Yet if Jersey was going to deliver on the order, it needed to assure a labour force for agricultural work.

By 1917, when conscription came into force, shortage of farm-workers was already a problem. At the start of the war, one of the main sources of labour had already left the island when thousands of French nationals departed to re-join their regiments. The mobilisation of the Militia, followed by the stead drain of volunteers, exacerbated the situation. The scene was set for a fight between Jersey’s farmers and the military authorities over Jersey’s men. Special tribunals sat through 1917 and 1918 hearing individual cases for exemption from the armed forces of the grounds of essential labour. In 1917, the farming community seemed to win the battle; Jersey retained enough men at home to reach UK government target for potato exports. In 1918, however, with the war dragging into its fifth and most bitter year things seemed likely to change.

The Final Push

On the battlefield and at home, the last year of the First World War was the most demanding. With both sides going all out for victory, military losses rose dramatically leading to calls for yet more men. Around Britain, a renewed German submarine campaign threatened to cause starvation, increasing the importance on exports from Jersey. And the cost of total war spiralled rapidly upwards. From Jersey, the British government demanded more: more men, more food, and more money. Wearily, Jersey set about providing all three.

In June, the upper age for conscription went up from forty to fifty years old. At the tribunals, the arguments became increasingly divisive as less and less men gained exemptions. Increasingly, it required the labour of women and foreign nationals to meet the increased government export quotas. Finally, the Jersey Government agreed to donate £100,000 pounds to Britain, a considerable sum of money for that time.

The Price of Victory

Given the strains to meet demands, the armistice in November 1918 that ended the war was a great relief to the island. Tempering the elation, however, was the cost of victory in terms of human lives and suffering. Jersey had sent over 8,000 of its men to fight in the war, with more than 1,200 killed in action, dying of wounds or succumbing to illness while in service. Thousands more returned with their physical or mental health ruined, many of whom would die premature deaths in years that followed. For a population of around 50,000 people, the legacy of the First World War would linger for many decades to come.

Recalling the First World War in Jersey Today

The dead of the First World War are the most readily visible reminder of that conflict in Jersey today. In mournful columns, their names adorn parish, school, and church memorials across the island. But in contrast to the Second World War, and its bunkers, walls and tunnels, tangible remains of the First World War in Jersey are harder to find. Yet they do exist.

Throughout the island, the legacy of the Jersey Militia abounds in the shape of former arsenals, barracks and firing ranges. Although most date from before the First World War, the Militia made extensive use of them as strongpoints, billets and training grounds during the years 1914-18. More directly linked with these years are two sites in particular. On high ground above St Helier called South Hill, there is a well preserved fortified gun battery established to guard approaches to St Helier’s harbour, while in St Ouen’s bay remains the mouldering outline of Blanche Banques POW Camp. The traces of old guardhouses, huts and ablution blocks are clearly visible among the dunes – an eerie legacy of Jersey’s forgotten history.

Find Out More About Jersey in the First World War

The Jersey Company is the subject of a recently published book and a dedicated website.